An independent review of NASA's ambitious mission to return about half a kilogram of rocks and soil from the surface of Mars has found that the program is unworkable in its current form.

NASA had been planning to launch the critical elements of its Mars Sample Return mission, or MSR, as soon as 2028, with a total budget for the program of $4.4 billion. The independent review board's report, which was released publicly on Thursday, concludes that both this timeline and budget are wildly unrealistic.

The very earliest the mission could launch from Earth is 2030, and this opportunity would only be possible with a total budget of $8 billion to $11 billion.

"MSR is a deep-space exploration priority for NASA," the report states. "However, MSR was established with unrealistic budget and schedule expectations from the beginning. MSR was also organized under an unwieldy structure. As a result, there is currently no credible, congruent technical, nor properly margined schedule, cost, and technical baseline that can be accomplished with the likely available funding."

The findings of the independent review, led by Orlando Figueroa, a retired deputy center director for science and technology at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, echo a report published by Ars Technica about three months ago raising serious questions about costs and schedule. The concern expressed by some scientists, including former NASA science chief Thomas Zurbuchen, was that the ballooning cost of Mars Sample Return would cannibalize funding from other science missions.

After the Ars Technica report, some policymakers in the US Senate also expressed serious concerns about the direction of the sample return program.

The mission

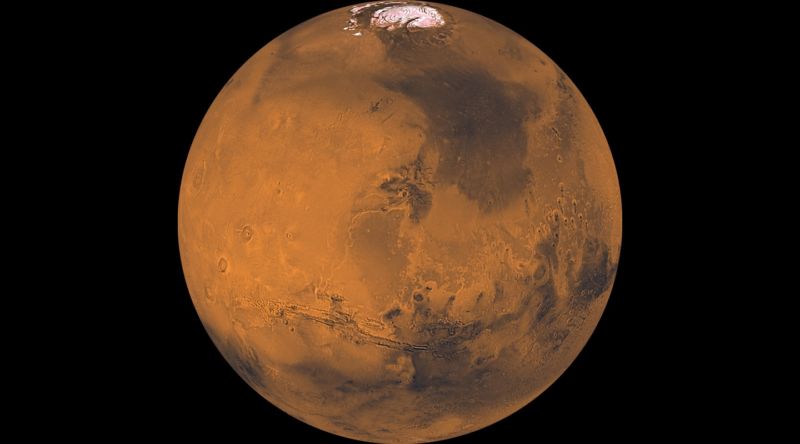

Under NASA's existing plan, the space agency will develop a large "Sample Retriever Lander." After this vehicle lands on Mars, the Perseverance rover—which has been collecting and storing samples of Martian dust in 38 titanium tubes, each the size of a large hotdog—will bring its samples to the lander.

Once delivered to the lander, these sample tubes will be placed aboard a rocket called the Mars Ascent Vehicle. This rocket is being developed by Lockheed Martin, and it will be stowed inside the lander. After launching from Mars, this rocket will release the "Orbiting Sample container" into Martian orbit, where it would be picked up by an "Earth return orbiter" built by the European Space Agency. This vehicle would carry the samples back to Earth orbit, where they would be released into a small spacecraft to land on the planet about five years after the mission's start.

As a backup plan, in case Perseverance is unable to deliver the samples to the lander, NASA proposed including two small helicopters like the Ingenuity vehicle to fetch the samples. The independent reviewers said a single helicopter would likely be acceptable.

reader comments

152